Water resources in your area

Water resources situation - November 2025

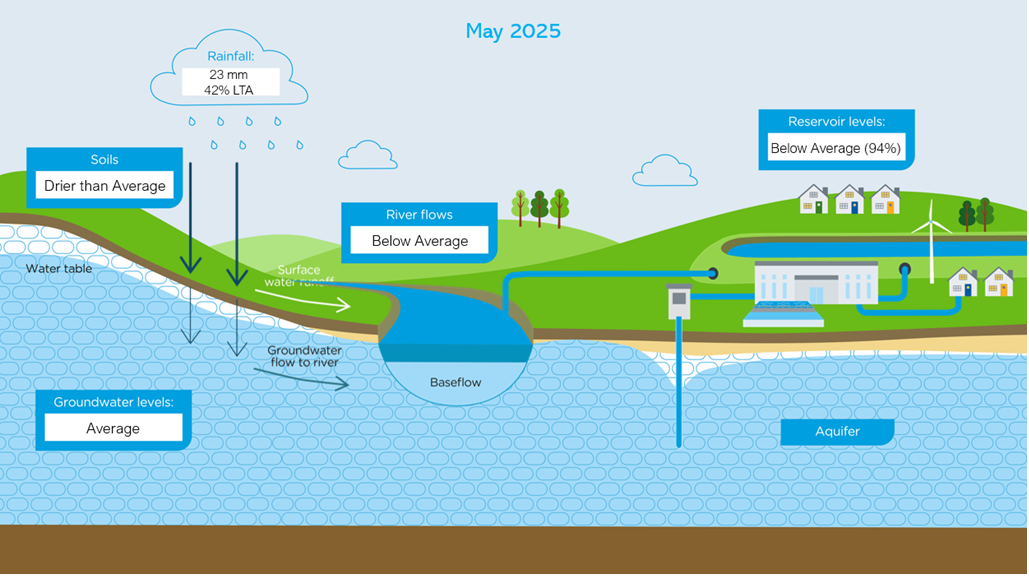

Check out our infographic to see our water resource situation at the end of November:

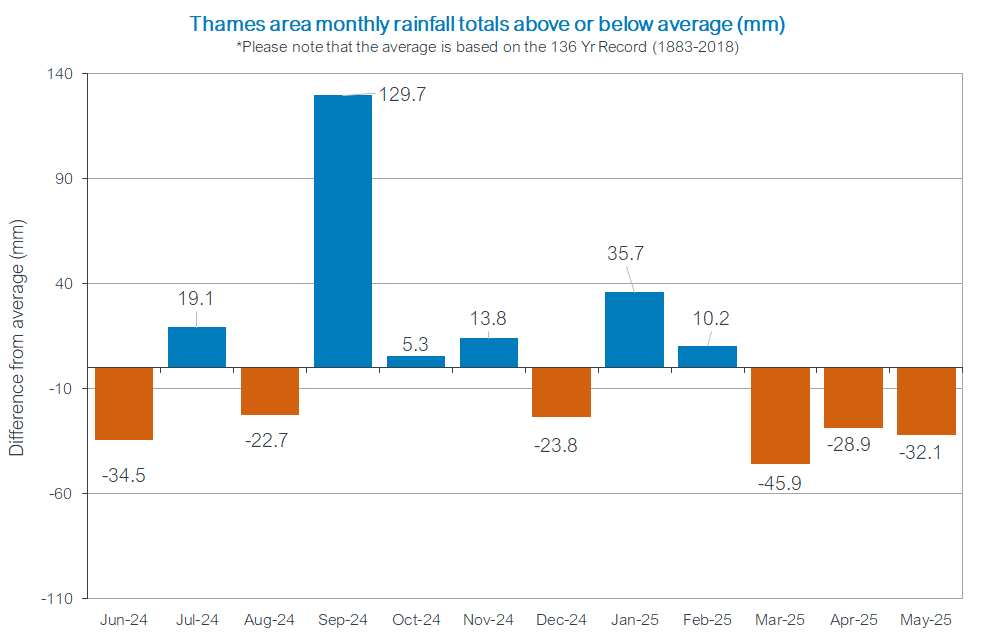

How much rain fell in our region?

In November, we experienced above average rainfall in the Thames Catchment. At 98mm, it was 129% of the long-term average.

The graph below shows how rainfall differs from the long-term average for the Thames catchment:

Soils in the Thames Region

Soils remained drier than average for the time of year across the Thames region by the end of November 2025.

Groundwater in the Thames Region

Groundwater levels were above normal in Swindon and Oxfordshire at the end of November 2025. They were mostly normal across the rest of the region. View our latest groundwater levels.

River flow in the Thames Region

In November 2025, river flows in the River Thames and River Lee remained average for the time of year. The Teddington Target Flow (TTF) moved to 800 Ml/d at the beginning of November, as agreed with the EA. This is in accordance with the Lower Thames Operating Agreement (LTOA).

Water levels in our reservoirs

At the end of November 2025:

- Reservoirs in London were 73% full (71% full in West London and 86% full in Lee Valley), which is below average for the time of year.

- Farmoor Reservoir in Oxfordshire was 93% full, which is above average for the time of year.

More about the current water resources situation

You can learn more about the status of water resources in the Thames region and beyond from regular Environment Agency reports.

Want to help save water at home?

It’s easy to assume water will always be there when we need it. But increased demand and our changing climate mean it’s more important than ever that we work together to save water where we can.

There are lots of ways you can do this, from turning the taps off when you’re brushing your teeth to using rainwater for your plants. Saving water helps protect the environment, including rare chalk streams – particularly during hot and dry weather when rivers, streams and the wildlife they support can be vulnerable.

Learn what we’re doing to protect this precious resource and how you can save water at home with our top water-saving tips.

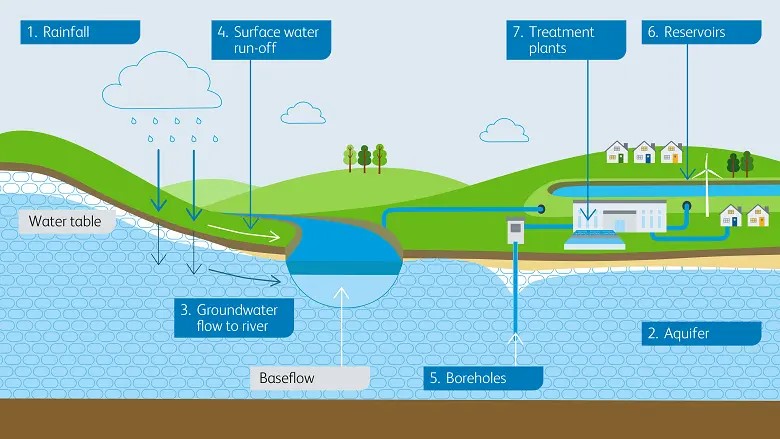

Where our water comes from

From morning showers to brushing our teeth at night, water plays an essential part in our day-to-day lives.

The clean water that comes out of our taps is taken from rivers and natural underground stores. The dirty water that leaves through our sewers is treated before we safely return it to the environment. This is all part of the water cycle – and rainfall is a vital part of it.

It may feel like it rains a lot in the UK, but did you know that our capital city gets less rain each year than Rome, Istanbul and even sunny Sydney?

- Rainfall: Rainfall soaks into the ground and tops up our groundwater. Natural underground stores of groundwater are key to our water supply and the water environment in our region. Groundwater levels vary throughout the year. During winter, increased rainfall produces higher levels, while summer and early autumn see levels fall naturally.

Temperature is also an important part of the water cycle as it affects how wet or dry the soil is across the Thames catchment. Warmer weather in the spring and summer encourages plants to grow and increases evaporation – this makes the soil drier. So, when it does rain, much of it is used by plants or evaporates. Into autumn and winter, when it’s cooler, the soil gets wetter and eventually becomes saturated. That’s when rain soaks further into the ground and starts to top up the natural underground stores. - Aquifer: Groundwater is stored naturally in layers of water-bearing rocks called aquifers. These are large underground layers of rock and other materials like sand and gravel, through which water can flow and be stored. In our region, chalk is the most important aquifer, but other limestones, sandstones and gravels also have a significant role.

The level to which aquifers fill and are saturated varies during the year and from year to year. This groundwater level is known as the water table. If there’s not enough rainfall in winter then the aquifers are not refilled and the water table remains lower in the aquifer. However, groundwater levels often respond slower to rainfall (or lack of it) than river flows. This helps reduce the impact of short, sharp dry periods on our water supplies - at least in the case of the chalk aquifer, but each aquifer in our region has different properties and can respond in different ways. - Groundwater flow to river: Groundwater may be out of sight, but it’s important for the environment as well as our water supply. When groundwater flows out of aquifers (sometimes via springs), it can make a big contribution to rivers and the wildlife they support. The aquifers also feed our rivers and help keep them flowing – this is called baseflow. During periods of low rainfall, it’s the flow of water from aquifers that maintains the flow of rivers.

- Surface run-off: Water flow in rivers also comes from surface run-off – rainfall that hasn’t soaked into the ground.

- Boreholes: We take groundwater from aquifers using boreholes and springs. The aquifers supply up to 30% of the water we use every day across London and the Thames Valley. But that’s not all they do – they also help keep our rivers flowing, which give us the remaining 70% of our water supply. When it gets drier, especially during drought, groundwater plays an even more important role, providing up to 40% of the water used across London and the Thames Valley.

- Reservoirs: We store water in large, open raw-water reservoirs before pumping it to our treatment plants.

- Treatment plants: Before it reaches your taps, we pump water from our rivers, aquifers and reservoirs to our treatment plants. This is to make sure it’s clean enough to drink.

River flows

River flows reflect groundwater levels and rainfall. Rain flows off the land and into the rivers, while groundwater can well up from below. Much of the water we supply comes from rivers in our region, including the Thames, Lee, Kennet, Wey and Tillingbourne.

When using these rivers, we need to make sure we balance environmental and necessary navigational needs with the needs of our water supply. We do this through agreements with the Environment Agency.

In London, the Teddington Target Flow is particularly important. This is the minimum River Thames flow over the Teddington weir required to balance these needs. Controls like this vary depending on the time of year and the amount of water stored in our reservoirs. They’re always agreed with the Environment Agency.

Saving for a (not so) rainy day

We store water, pumped from the River Thames and River Lee, in large reservoirs in Oxfordshire, West London and North London. In North London, we top up the reservoirs with groundwater pumped from the chalk aquifer.

The raw water in our reservoirs and rivers is clean enough to support a variety of wildlife, but not safe enough to drink. Before it reaches your taps, we pump the raw water to our world-class treatment sites for cleaning.

We carefully monitor water levels in our reservoirs and regularly inspect and maintain them to safeguard your supply.

Our reservoirs are home to a diverse range of wildlife, and many are open for the public to enjoy. Learn about visiting our reservoirs and nature reserves.